Flowing-retail: Demonstrating aspects of microservices, events and their flow with concrete source…

Originally published on blog.bernd-ruecker.com

Flowing-retail: Demonstrating aspects of microservices, events and their flow with concrete source code examples

Discussing architecture concepts or paradigms is half the fun if you cannot point to concrete code examples. Runnable code forces you to be precise, to think about details you can leave out in Power Point and most importantly it can explain things very well. True to the motto “the architect always implements” I assembled a running sample application together with my friend Martin Schimak. We tackle paradigms like microservices, domain driven design and event driven architecture.

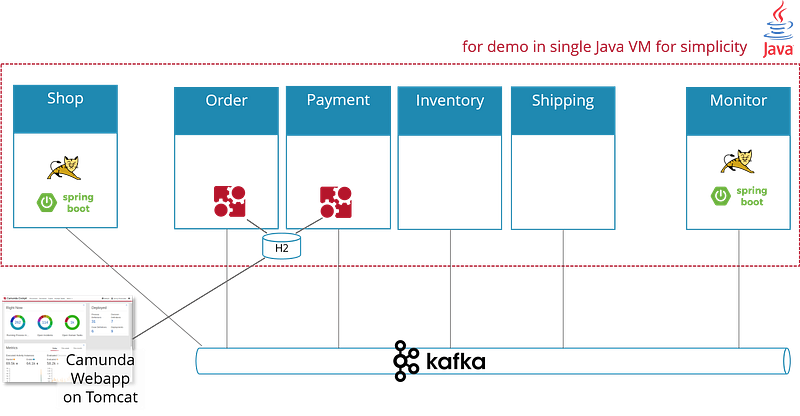

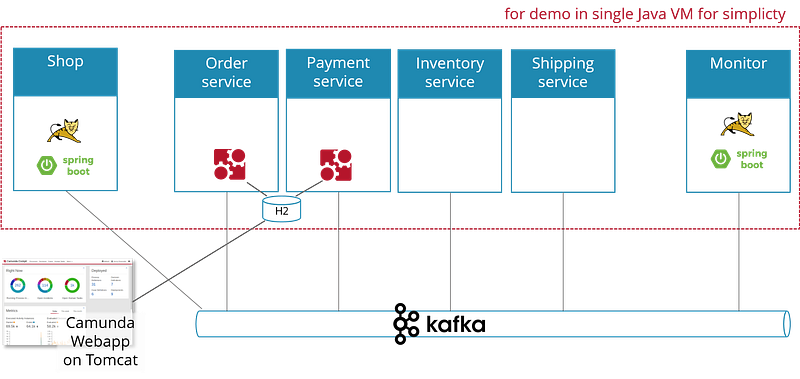

We selected a simple order process as this is a domain everybody knows. We designed it to have the following microservices:

- **Inventory **(handles stock and picking of goods)

- **Shipping **(handles shipments and logistics)

- **Payment **(you guessed right)

- **Order **(caring about the overall order)

- **Shop **(sample shop to place order)

- **Monitor **(sample web app listening to all events to display them)

All services are separated into their own components. Technically speaking they are Java Maven projects, independently runnable.

The components communicate via **messaging **with the option to use either RabbitMQ or Apache Kafka as a channel.

Where do I find it?

You find it on GitHub: https://github.com/flowing/flowing-retail, follow the readme to get going.

We start to collect thoughts and material around it on http://flowing.io.

How do I run it?

As the example is developed in Java you will need Java and Maven on your local machine. Then you can run the whole example by typing one single command, check the readme on GitHub for details.

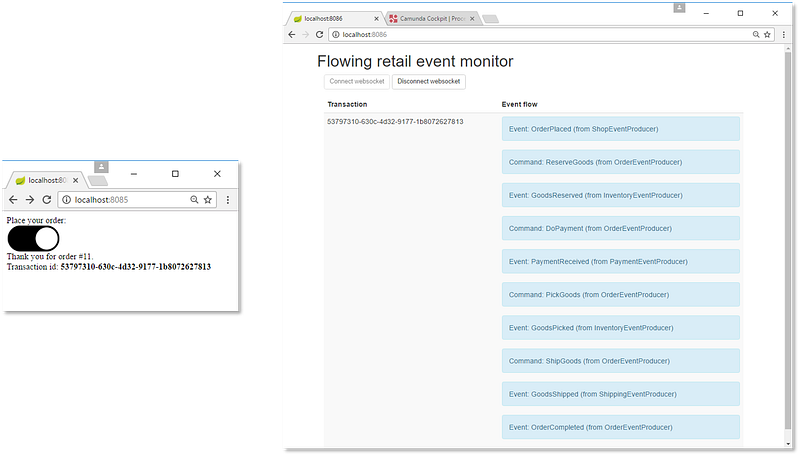

Afterwards you can access the shop application (it might remind you of Amazon Dash?). After ordering you can watch the flow of events and commands happening in order to get the business process finished. That’s it. Not much too see on the outside but more to see on the inside!

Architecture

Every microservice has their own Maven project. We kept them as simple as possible. We preferred naive implementations which are easy to read over sophisticated solutions. The project is not intended to be used in production.

You can choose between alternatives for:

- Transport: You can use Apache Kafka or RabbitMQ. The concrete tool does not matter much for our goals. As default all communication is done via Apache Kafka.

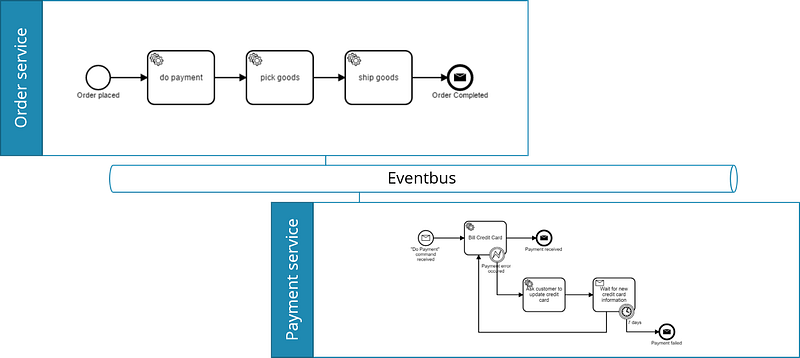

- Implementation for long running flows: We show the different options highlighted in Implementing long running flows. One option is to handle the state via domain entities, another option is to use the Camunda engine. In the latter case the engine is started as part of the microservice, so we avoided any central BPM component to not violate microservice principles like freedom of technology choice and being independently deployable.

The picture shows the default demo setup of the application. It starts all components in one Java VM to avoid a complex startup procedure. However, you can start every service separately if you like. Two Camunda engines will be started as two Microservices need to take care of long running flows at the moment. So yes, every service starts its own engine. These engines run headless. In the demo setup they point to the same database as this makes it very easy to point to one monitoring tool to this database and have a central view on all business processes. With Camunda this works smoothly as the engines know which flows they touch — and which not. Also Camunda supports rolling updates meaning you can always run two versions of Camunda on the same database. That means you do not have to upgrade all microservices in one go — but do it step by step. However, if your goal is for total decoupling you better use one database (or database schema) per engine. I have seen both approaches running successfully in real-life.

I want to emphasize this important aspect: Even when using an orchestration engine (you might also call workflow or BPM engine) you do not have to introduce a central component. The engine can be part of the microservice itself. It is “just” a library to help in implementing the microservice. The overall end to end business process is split into parts owned by the microservices, and choreographed (I will dedicate an entire blog post to this topic). This is different to most BPM approaches which try to model one end-to-end-process (I already mentioned this in the 7 sins of workflow recently). But in our example the payment process is a black box to the order process expert.

Related patterns and thoughts

The demo application shows a lot of patterns and thoughts in action for example:

- Implementation options for long running flows

- Event Command Transformation

- Thoughts on orchestration and choreography

- Distributed process ownership

Expect more detailed blog posts to follow.

Happy coding!

The sample application is meant to help you — and to get discussions going. So try it out and let me know if you have feedback, questions or want to discuss!

Stay up to date with my **newsletter*.*